Give a first-grader the chance to pick a theme for his birthday party and what will he choose? Super-heroes? Monster trucks? Star Wars? Or, as recently happened in the eastern corner of the state of Tennessee, a Colonial Times birthday party, featuring soap-making and eating cake by candlelight.

What inspired that theme? The curriculum chosen by the student’s school district, Sullivan County. The district is now in its third year of using Core Knowledge Language Arts® (CKLA) to strengthen early literacy instruction.

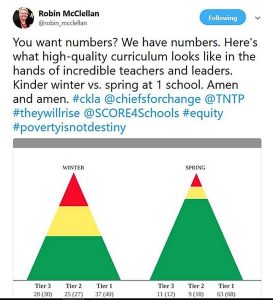

Sullivan County’s Supervisor of Elementary Education, Dr. Robin McClellan, is excited about the promising early results. Sullivan County is a mostly rural Appalachian district, with more than 60 percent of its elementary school students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Over the course of the 2017-2018 school year, Dr. McClellan notes, many students who were initially identified as academically at risk—in the lower tiers correlated to the benchmarks of the aimswebPlus progress monitoring tool—advanced to Tier 1 and are no longer at risk. (See Dr. McClellan’s Twitter post about the representative results at one school.)

Sullivan County’s efforts reflect a general statewide focus on strengthening early literacy instruction, and are specifically tied to LIFT (Leading Innovation for Tennessee), a network of twelve Tennessee district superintendents focused on “new classroom strategies, practices, and curriculum to improve reading in the early grades.” LIFT receives support from SCORE (State Collaborative on Reforming Education), an independent, nonprofit, and nonpartisan educational research and advocacy group based in Nashville.

Sullivan County’s efforts reflect a general statewide focus on strengthening early literacy instruction, and are specifically tied to LIFT (Leading Innovation for Tennessee), a network of twelve Tennessee district superintendents focused on “new classroom strategies, practices, and curriculum to improve reading in the early grades.” LIFT receives support from SCORE (State Collaborative on Reforming Education), an independent, nonprofit, and nonpartisan educational research and advocacy group based in Nashville.

According to Courtney Bell, SCORE’s Director of Educator Engagement, after SCORE worked with the LIFT districts to identify targets for improvement, they decided to focus on strengthening early literacy by “providing more universal access to high-quality curricular resources for teachers” and “making sure that school leaders understand what strong literacy instruction looks like, so they can prioritize the time, the resources, and the support that teachers need to implement with fidelity.”

SCORE has helped schools in the LIFT network identify high-quality, standards-aligned resources—a task made more pressing and challenging when, in 2016, the state adopted new and more rigorous academic standards. Tennessee is a textbook adoption state, but the last adoption took place in 2010. So, Mrs. Bell notes, “many districts are using materials not aligned to the state’s new college- and career-ready standards.”

To help LIFT districts fill the gap until the next ELA adoption in 2020, SCORE engaged TNTP as a “technical assistance provider.” (Founded in 1997 as The New Teacher Project, TNTP now works as a partner for change in more than 200 public school systems nationwide.) In instructional reviews of classrooms across the LIFT districts, TNTP found that in most K-2 classrooms, text complexity was too low and students spent very little time thoughtfully interacting with the text. TNTP then undertook a national search for high-quality early literacy curricular materials, especially ELA programs with strong read-aloud components. In 2016, TNTP identified only a few qualified programs, including CKLA; since then, the list has grown to include Expeditionary Learning, Wit and Wisdom, and other options.

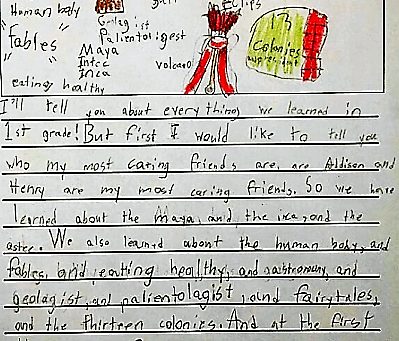

“The big thing we’ve learned,” says Mrs. Bell, “is how critically important systematically building knowledge is for kids, particularly kids who may come from an impoverished background or not come from a well-resourced home. Having high-quality instructional materials that systematically build knowledge over time really is an equity issue. It allows the playing field to be leveled for all kids so they are able to succeed. Kids really rise to the occasion—it’s just been so miraculous to see.” (For one example, see the student work samples from Sullivan County first-grade teacher Lize Kinsler, which compares one student’s first day writing sample to her writing at the end of the school year.)

On the first day of class, this first-grader wrote fragments about “drinking jitter juice.” At the end of the school year, she wrote complete and excited sentences: “So we have learned about the Maya, and the Inca, and the Aztec. We also learned about the human body, and fables, and eating healthy, and astronomy, and geologist, and palientolegist [sic], and fairy tales, and the thirteen colonies.”

A recent statewide survey of Tennessee educators revealed that K-2 teachers spend an average of 4.5 hours per week in sourcing ELA materials—“that’s four and a half hours,” notes Mrs. Bell, “that they’re not planning how to differentiate instruction or not really digging in so they can have a strong understanding of the content.” Mrs. Bell argues that “we have to stop expecting teachers to be curriculum curators. If you just give teachers the materials they need, and allow them to do what they do best, which is to teach and to lead learning, then that really has a dramatic impact on student learning.” In short, Mrs. Bell summarizes, “Knowledge matters, and teachers need high-quality materials.” Sullivan County’s Dr. McClellan agrees: “The conductor of an orchestra doesn’t write the score. Now that our teachers have strong curriculum in their hands, they are able to focus on the students’ learning.”

In most LIFT districts, schools began by piloting the recommended curricular options and then choosing their preferred program for expanded implementation. Sullivan County was drawn to CKLA for reasons both pedagogical and practical. First, as Dr. McClellan explains, CKLA filled two big gaps in the county’s existing ELA curriculum: “lack of explicit skills instruction, and lack of knowledge building.” Second, the Core Knowledge Foundation makes CKLA available as Open Educational Resources, which helps when, as Dr. McClellan recalls, “we didn’t have the resources to purchase new literacy curriculum.”

Mrs. Bell, who has worked closely with Dr. McClellan, praises Sullivan County for “the way that they’ve empowered their teachers to lead the learning.” Initially, three Sullivan County schools piloted CKLA. TNTP helped train the teachers in these three pilot schools. In the second year of the initiative, these pioneering teachers, dubbed “Game Changers,” took on the responsibility for training the “Difference Makers,” the teachers in the remaining eight elementary schools in the district.

Both SCORE and TNTP have worked to ensure that the early literacy initiative is “deeply embedded” so that it continues even when district leadership changes. “We want to make sure the work is sustainable,” says Mrs. Bell: “We’ve had a couple of districts undergo leadership changes at the district level and so far the work has continued seamlessly because there is such strong buy-in from the school leaders and other district-level staff and the teachers as well.”

SCORE insists that district leaders roll up their sleeves and actively participate in understanding the nuts and bolts of effective early literacy instruction. Four times per year, SCORE convenes LIFT superintendents to meet in one of the participating districts, where they visit classrooms and then use an instructional rubric to guide discussion of the strengths and shortcomings of the teaching they observed. The goal, says, Mrs. Bell, is to “make sure everyone has a vision for high-quality literacy instruction.”

Instructional leaders at work: A group of Sullivan County principals discuss the CKLA lesson they have just observed.

Similarly, in Sullivan County, once a month all eleven elementary school principals gather at one of the school sites. They break into teams to observe teachers and students engaged in a specific CKLA domain. Guided by the same rubric that the superintendents use, the principals then gather as a group for discussions that lead to practical feedback to the teachers, for example: “We saw these strengths, let’s celebrate these things, and why don’t you visit Mrs. B’s classroom to see how her questions lead to enduring understanding.”

In early 2018, after visiting one of these gatherings at a Sullivan County school, Core Knowledge Foundation President Linda Bevilacqua noted the shared commitment to involving instructional leaders in understanding the curriculum and providing feedback to teachers. “In building the competency of instructional leaders,” says Ms. Bevilacqua, the Sullivan County schools, with SCORE and TNTP, are “building lasting infrastructure—even when trainers leave, there will be lasting understanding of the program, with teachers trained as mentors and coaches.” As Dr. McClellan affirms, “We’re just all in it together.”